The biggest attraction in Belfast was Titanic Belfast which stood right next to the original slipways where the Titanic was built. More than six stories tall, the building was covered in more than 3,000 sun-reflecting panels. The imaginative building's four corners represented the bows of many ships, most of which didn't sink, that were built in these shipyards during the industrial Golden Age of Belfast. The attraction was divided into nine galleries on six floors.

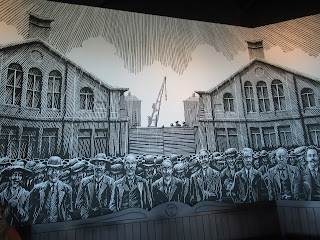

The first exhibit was Boomtown Belfast. During the Great Potato Famine of 1845-1850, people from all over Ireland moved to Belfast to find work. The decline of the rural economy coincided with growing prosperity in Belfast. Women moved for more independence and higher earnings. Between 1851 and 1901, the city's population increased from 87,062 to 349,180.

During the 19th century, people flooded into Belfast to work in the linen mills. By 1900, Belfast was producing and exporting more linen than anywhere else in the world. Belfast became known as 'Linenopolis' as many processes were carried out in the city's linen mills.

In 1784, the White Linen Hall was built in Belfast as local merchants attempted to take control of the linen trade from Dublin. With industrialization, the linen industry began to be centered around Belfast. There was a ready supply of labor and Belfast had the infrastructure to facilitate the growth of industry. The city's River Lagan had tributaries which could drive the machinery and provided routes to collect linen, Finished products were then exported through Belfast docks.

The different processes which went into making linen meant there was a series of different jobs within the mils. In 1900, over 65,000 people worked in linen mills in Ireland with most in Belfast. Employees worked six days a week for a low rate of pay. Most were women who became known as Millies. They often continued to work after marriage, during pregnancy, returning to work shortly after childbirth. Children were also employed in the mills, working half-time and therefore known as half-timers.

Shipbuilding grew to be a major industry in Belfast, and, as it did, so did the need for a large and reliable supply of rope. The Belfast Ropeworks was established to meet this demand, replacing a number of smaller companies.

Manufacturing Belfast aerated waters: In the mid 1800s, there were several small firms producing 'aerated waters' or soft drinks.

Working in industrial Belfast: By the early 1900s, Belfast had developed a range of successful and inter-connected industries, employing large work forces. Working conditions varied across the range of industries and within each industry. Many of Belfast's industries were related to each other. For example, the rope works supplied the shipyards and textile engineering firms supplied machinery to the linen mills. The job held by an individual dictated his or her social standing. Apprentices to trades worked a long apprenticeship but once qualified, they gained statues as skilled workers. Some industries, such as shipbuilding, were dominated by men while the linen mills employed mostly women and children. Men were paid a higher wage than women or children. In 1901, 24 percent of Belfast's population was Catholic. A relatively large proportion of Catholics worked in the unskilled, poorly paid, irregular and dangerous jobs. Political differences between workers and continual migration into Belfast from rural areas contributed to the slow development of labor movements and unions.

Belfast docks played an important role in the city's economy. They were crucial for the import of raw materials for industry and to export products around the world.

Belfast was the fastest cargo discharging port in the world. In 1907, there were over 6,000 people working as dockers and carters in Belfast's docks. Work at the docks was low-paid, dangerous, physically demanding and often casual which meant no job security.

In the first decade of the 20th century, more than eight million Europeans emigrated to North America. New York was the main gateway to a new life. Most emigrants looked for a better standard of living. Poverty, lack of land, adventure and opportunity were all reasons to leave. North America welcomed immigrants as skilled workers for its industrial cities and farmers for its prairies. Importantly, people were free to practice their religious and political beliefs.

By the 1900s, there were two main competitors for the North Atlantic passenger trade: the White Star Line bought by American millionaire J. Pierpoint Morgan in 1902 and the British-owned Cunard. The race to build larger, faster and more luxurious ships intensified with White Star's ambitious plans to build three Olympic class ships which were large enough to carry hundreds of emigrants but luxurious enough to attract the wealthy.

Bruce Ismay was chairman of White Star Line and placed the order for the Titanic with Harland and Wolff, the major shipbuilders in Belfast.

When the Olympic class ships were commissioned, Harland and Wolff was one of the largest and most successful shipyards in the world. It employed thousands of Belfast men. Full and quarter scale sections of the ship were sketched out in their drawing offices.

The journey from design to construction was a complex one for the Olympic class ships. The ships were planned with a series of two-dimensional flat plans and three dimensional models. Once completed, the designs were taken to the mould loft which was several hundred feet long and a hundred feet wide. On its floor, loftsmen would chalk the lines of the cross section of the ship at full-size and the length at quarter size. Any corrections were then updated on the plans. The loftsmen also made templates for all the structural parts of the ship.

There were 254 recorded accidents with 8 fatalities during the construction of the Titanic. When a man died on the job, the saying was "He's away to the other yard." Shipyard workers brought their own food to work with them; this was known as their 'piece.' The workers had a one week holiday in the summer and two days off at Christmas and Easter.

The building of the Titanic began on March 31st, 1909. At the same time as the ship was being built, Harland and Wolff were busy making machinery and fittings that would be installed after her launch. It took 26 months for the structure of the Titanic to be completed.

Altogether, over three million rivets were used on the Titanic!

There were 15 watertight bulkheads that ran across the Titanic in the lower decks. These divided the ship's hull into 16 watertight compartments.

After it was launched from its building blocks at 12:13 pm on May 31, 1911, the largest moving object built by man began to be moved for the first time. Amid cheers from the assembled crowd, the hull gathered speed, estimated at 14 mph, as it entered the water. She traveled almost twice her length in 62 seconds. 130,000 people watched the launch of the Titanic and then celebrated the huge achievement at local pubs.

From the museum we had a great view to the slipways where the Titanic had been built.

The Titanic was described as the Queen of the Ocean. The first class cabins would have been occupied by extremely wealthy people such as members of the aristocracy or very successful business people. The cabins were fitted with windows letting in natural light and electric lights including a portable table lamp, wall and ceiling lights. Carved oak paneling and wallpaper coverings adorned the walls.

First class areas were very luxurious and were comparable with the best hotels of the time. There was a range of amenities available including a choice of dining, sporting, exercise and leisure facilities. The dining saloon was decorated in early 17th century Jacobean style with detailed ceiling plasterwork, oak furniture and a piano.

Second class facilities included a dining saloon, promenade deck, smoke room and a library. The dining room was decorated in Early English style, using oak and decorative canopies above the doors.

The Titanic could accommodate 945 crew members: 61 in the Deck Department such as bridge officers, quartermasters, etc; 317 in the Engine Department including engineers, firemen, etc; and 507 in the Victualing Department such as stewards, barbers, cooks and waiters.

The Titanic needed huge quantities of linen for her journey. Her table and bed linens, patterned with the White Star emblem, were made in the major linen producing area around Belfast. The Titanic carried thousands of aprons and tablecloths and over 10,000 cloths for use in the food preparation areas, plus 18,000 bed sheets and 45,000 table napkins. As there were no facilities on board to wash linen, the ship needed to carry all the linen for the voyage with her.

After successfully completing her sea trial in Belfast, the Titanic set sail for Southampton on April 2, 1912. On her delivery voyage through the Irish Sea and English channel to Southampton, the Titanic recorded a speed of a little over 23 knots, the highest speed she would ever attain.

The last message:

The press took to tugs, ferries and launches - anything that floated - in their pursuit of stories as the Carpathia headed up the Hudson River. They urged passengers to send messages in bottles or jump on their boats. They offered to buy survivor stories. The full horror of the Titanic disaster was revealed when the Carpathia docked late on April 18th.

Crowds awaited the Titanic survivors in New York. Watched by a crowd of 30,000, Carpathia arrived at Pier 54 in New York after dropping off the Titanic's lifeboats which later mysteriously disappeared. Many survivors were too exhausted, injured or shocked to appreciate the sensation their arrival caused. Some claimed that everyone could have been saved if there had been enough lifeboats.

Coverage of the disaster was strongest in cities associated with the Titanic - Belfast, Liverpool, Southampton, New York and Halifax. As the sinking ceased to make headlines, the press turned to stories of local people who played a role in the Titanic. The press studied passenger lists looking for millionaires and featured the fate of celebrities. Although the death rate was much higher among Third Class passengers and crew, their stories went largely untold.

The Aftermath: The British Inquiry that opened on May 2nd was longer and more formal than the American investigation and relied more on maritime experts than on the memories of survivors. Over 38 days, a battery of lawyers examined 97 witnesses, seeking answers to 26 specific questions covering construction, operation, the sinking and the rescue.

Other recommendations were that ships slow down or change course at night after ice warnings; all foreign-going passenger and emigrant ships needed to operate the wireless 24 hours a day; and more thorough lifeboat inspections and better training by the crew.

Only two days after the disaster, there was an US Senate Inquiry in which passengers and crew were questioned in an attempt to find out exactly what happened and why. The Inquiry lasted 18 days and questioned 86 witnesses from the lookouts to some of the last men to jump from the sinking ship. Following the inquiries, laws were passed to improve safety at sea. Except in wartime, no lives have since been lost due to icebergs.

As a result of the American inquiry, passengers were advised of their lifeboat station and crews received regular training in lifeboat drills; everyone was guaranteed a place on a lifeboat; all lifeboats were required to carry food, water, a compass and other equipment; passenger ships were required to be evacuated within thirty minutes in the event of an emergency; and all ocean-going vessels had to have a radio room manned 24 hours a day.

I was surprised to learn how well the Belfast shipbuilding firm, Harland and Wolff, did in the decades after the Titanic disaster. The yard won orders to bring passenger ships up to the new safety requirements and later to build warships. By the 1920s, Harland and Wolff employed 65,000 people at five British shipyards and had massive engine-building and iron-casting works and a new yard to mass produce ships to a standard design. The Depression and the end of the relationship with White Star were offset by a growing naval order and a joint venture to build bombers. During WW II, the yard built over 130 warships, repaired many more and manufactured armaments.

When air travel and overseas competition led to the decline of British shipbuilding, Harland and Wolff concentrated its operations in Belfast in the 1960s. It has since moved into new markets from offshore oil to renewable energy and the company remains a significant engineering business in the city to this day.

Myths and reality: The way that films have presented the Titanic's last hours has shaped how people think and feel about what may have happened on board. In 1943, the Nazis made the film Titanic showing the British as greedy cowards and the Germans as brave. The hero was a German officer who rescued Third Class passengers. The villain was Bruce Ismay, the head of the White Star Line, who wanted to break the speed record to profit from a share swindle.

The 1929 film Atlantic was released in many versions, one of them silent and in English, French and German with sound.

Above all, Titanic was about romance if you recall Jack and Rose's passionate last kiss in the 1997 version that starred Leonardo DiCaprio and Kate Winslet! The film could also be seen as a contrast of fabulous wealth and happy-go-lucky poverty with Rose escaping from the luxurious tedium of First Class to join Jack in an Irish jig in Third Class.

In 1985, while leading a Franco-American team, Robert Ballard, an marine archaeologist, oceanographer and former US naval officer, discovered the wreck of the Titanic, two and a half miles below the North Atlantic.

One wall displayed the name, ship number and launch year for each of the 401 ships built by Harland and Wolff up to and including the Titanic.

I can't remember when we'd spent so much time at any museum or attraction before as we did at Titanic Belfast. The entire experience had been engrossing, and didn't only dwell on the ship building and the eventual sinking of the Titanic but on the huge growth of Belfast in its Golden Age and, importantly, the measures taken to ensure such a tragedy could not occur again. Hours went by with our being hardly aware of the passage of time - the testament to a superb museum.

Next post: Discovering Belfast's Ulster Folk Park, sort of like Colonial Williamsburg and Upper Canada Village for my American and Canadian readers, respectively!

Posted on October 31st, 2019 from a snow-covered Denver on Halloween!

In 1861, the outbreak of the American Civil War caused disruption to the supply of American cotton. This led to an increased demand for linen. The number of mills in and around Belfast grew quickly in the mid 19th century to meet this demand. Before industrialization, the process of growing, harvesting and turning flax into linen took place in the countryside. By the 17th century, this was an important industry in the north of Ireland.

Working conditions and health hazards varied from job to job. Dust inhaled when preparing flax could trigger lung disease. The hot humid conditions needed for spinning and weaving caused chest infections. Working barefoot in water in the spinning rooms often led to painful foot conditions.

Throughout the mill, there was the ever-present danger of serious injury or death from accidents with machinery. The final stages of the process, such as embroidering, commanded low pay but were carried out in healthier working conditions and were regarded as socially superior.

There were two large tobacco companies in Belfast: Murray's and Gallahers. By the early 20th century, Gallaher & Co, on York St. was the largest tobacco firm in Ireland and employed more than 1600 people.

Before 1860, Dunville's had been one of the leading tea merchants in Ireland. But they stopped trading in tea to concentrate on whiskey blending. Prior to opening the Royal Irish Distilleries, Dunville's didn't distill their own whiskey. Instead, they blended whiskeys from other distillers.

When they opened the Royal Irish Distillers, there was no other substantial distillery in Belfast. The Royal Irish Distillery was a huge modern plant that produced 60,000 gallons per week. By 1900, Belfast produced 60 percent of Irish whiskey exports.

From the 1700s, Belfast was importing sugar, tobacco and agricultural produce through the docks. Belfast lacked access to local raw materials and energy supplies which were vital for industrialization. Coal was imported from England. A major export through the docks was linen and other locally manufactured goods including cigarettes, whiskey and aerated waters. The duty paid on goods passing through Belfast's docks was important for the government's revenue. Ships built in Belfast were used to import and goods worldwide.

Travel, communication and emigration: The world was changing rapidly in the late 19th century. Emigration produced one of the greatest recorded movements of humanity. At the same time, faster ships and new ways of communicating made the world seem smaller.

Belfast grew rich building emigrant ships to ever higher standards. Third Class replaced steerage and the days of the 'coffin ships' were long gone. There were cabins rather than dormitories and toilet facilities were adequate. Emigrants no longer needed to bring their own food as they were served a choice of food in large dining halls. Better-off emigrants could afford to travel on White Star and Cunard's express service from Southampton in southern England. By 1910, the city was one of Europe's main departure points along with ports in Germany and Italy. My own mother emigrated from England via Southampton to Canada after marrying my father in 1946.

In order to build the new Olympic class ships, many improvements were made to the shipbuilding facilities in Belfast. The slips in the north yard and extension of the Arrol Gantry were required for building Olympic ships and the Titanic.

A hokey experience known as the Shipyard Ride was a low-speed journey through the Harland and Wolff shipyard that included changes in height, visual and audio effects as if we had been transported back to the early years of the 20th century to capture what it might have been like to be a worker building the Titanic.

Ordinary doors such as these in most passenger areas were a point of weakness.

The bulkheads were connected to the shell plating. The collision bulkhead was located at the bow of the ship and fitted to be an airtight watertight skin should the bow be damaged in an end-on collision. The ship was designed to stay afloat if up to three of four forward compartments were flooded. The Titanic had eight passenger decks and ten decks total.

On board, the Titanic had a huge array of rooms and facilities. The first, second and third class public areas were separate and decorated very differently.

Second class facilities included a dining saloon, promenade deck, smoke room and a library. The dining room was decorated in Early English style, using oak and decorative canopies above the doors.

The majority of Third Class passengers were emigrants heading to America for a better life and therefore would generally have been going on a one-way ticket. The cost of a third-class ticket from Queenstown to New York was equivalent to almost a month's wages for skilled Harland and Wolff workers. Third class public areas were basic but superior to those on most ships at the time and included a dining saloon, smoke room and promenade.

This is probably how some of the crew accommodation looked like on the Titanic.

White Star Line tableware:

The Titanic struck an iceberg on April 14th, 1912, just four days after its maiden voyage and sank with the loss of over 1,000 lives at 2:20 am on April 15th, 1912. Reading the telegrams sent by the ship's captain after the Titanic hit an iceberg was chilling.

The Carpathia was the first ship to reach the scene of the disaster and picked up 713 survivors from the lifeboats and made for New York. Arthur Rostron, captain of Cunard's line Carpathia was heading from New York to the Mediterranean when he was told of the Titanic's distress signals. He turned his ship around and went to the Titanic's aid. At 4:10 am, a lifeboat was sighted and the first passenger rescued informed Carpathia's purser the Titanic had sunk. Four hours later, the Carpathia had found the 20 lifeboats and rescued 713 passengers and crew. Although Halifax, Canada, was the nearest port, Rostron made for New York to avoid the risk of icebergs and further distress the survivors.

Lack of information led to conflicting rumors about the Titanic's fate. Carpathia's radio operator worked nonstop forwarding the names of survivors and sending messages to relatives, but ignored press inquiries. However, any radio enthusiast could 'listen in' and spread rumors. On April 15th, a Marconi operator picked up a message that the Titanic was sinking and told the press. Some newspapers reported the Titanic was heading for Halifax with everybody safe. Although Rostron urged the head of White Star Line to inform the public of the disaster, the company's vice president told the press that the Titanic couldn't sink. Only after a message from the Carpathia to New York was received did the scale of the tragedy start to unfold.

The press took to tugs, ferries and launches - anything that floated - in their pursuit of stories as the Carpathia headed up the Hudson River. They urged passengers to send messages in bottles or jump on their boats. They offered to buy survivor stories. The full horror of the Titanic disaster was revealed when the Carpathia docked late on April 18th.

The news of the disaster spread around the world.

The city of Belfast mourned its dead and the loss of the ship on which so many workers had left their mark. Anxious relatives waited to hear whom among the survivors were their kin.

The British Inquiry made 24 recommendations to avoid such a disaster from happening again. It concluded the loss of the Titanic "was due to collision with an iceberg, brought about by the excessive speed at which the ship was being navigated." A major recommendation was that lifeboat and raft accommodation be based on the number of people instead of tonnage.

The 1929 film Atlantic was released in many versions, one of them silent and in English, French and German with sound.

The 1953 version won an Oscar for their screenwriting.

Surrounding the Titanic's wreck was a debris field of thousands of individual items from the ship. It was this debris that helped Ballard located the Titanic. The artifacts ranged in size from a huge ship's boiler to kitchen equipment and personal belongings. Although many items have disappeared over the decades, after a century underwater there were still remarkable items that survived.

I read there were no actual artifacts from the underwater wreck out of respect for the fact that the site was a mass grave.

The memorial outside was built in honor of the men, women and children who lost their lives during the sinking of the Titanic. The lampposts marked the size of the Titanic that had been built right here.

Next post: Discovering Belfast's Ulster Folk Park, sort of like Colonial Williamsburg and Upper Canada Village for my American and Canadian readers, respectively!

Posted on October 31st, 2019 from a snow-covered Denver on Halloween!

No comments:

Post a Comment