Right by our B&B in Trim, a small town north of Dublin, were the ruins of Bective Abbey, a Cistercian abbey founded in 1147. It was used as a location during the filming of the historical action drama Braveheart featuring Mel Gibson. Though filmed in Ireland, it was actually about Scotland’s, not Ireland’s, fight for freedom from the British.

Next post: Onto Wales by ferry and a whistle stop tour through the northern part of the country.

Posted on March 11th, 2020, from Anuradhapura in northern Sri Lanka before heading south in the morning for our last day in this country and, we hope at least, continuing our long adventure through Asia and the Middle East in the age of the coronavirus!

In the gray morning drizzle, we walked around the towering ruins of Trim Castle, the biggest Norman castle in Ireland, before it opened up. The castle, which replaced a wooden fortification that was destroyed in 1173, was completed in the 1220s. The impressive castle was also used in the filming of Braveheart. The gatehouse was built high above the moat around 1180 and then rebuilt in the 13th century.

While Steven rested in the car, I traipsed along a footbridge to see the Yellow Steeple over the river from the castle. That was all that remained of the 14th century Augustinian Abbey of St. Mary.

I guess the steeple or tall bell-tower which was badly damaged in the 17th century wars must have been yellow at one time but there was no evidence of it I could see.

A statue of the Blessed Virgin Mary known as the Idol of Trim was venerated here in the Middle Ages but was destroyed during the Reformation.

A better view of Trim Castle once the rain let up:

Some photos I took as I strolled back through town:

Near the town center was the 30-foot tall Wellington Column that honored native son Arthur Wellesley who defeated Napoleon at Waterloo and who twice became prime minister.

More castle views from the Barbican Gate which was constructed early in the 13th century to guard the southern approaches to the castle. An elaborate system of lifting bridges, gates and overhead traps gave the guards great control over those who sought entry to the castle.

Rather than driving directly to Dublin, we drove thirty minutes in the opposite direction to the Battle of the Boyne site which felt a bit like Gettysburg on approach. Though the site is one of Europe’s lesser known battle grounds, it is huge in Irish and British history. In the deciding battle, the Protestant British decisively broke Catholic resistance over all of Ireland and Britain.

It was here by the present village of Donore in 1690 that the Protestant King William III with his English/Irish/Danish/Dutch and French Huguenot army defeated his father-in-law and uncle, Catholic King James II, and his Irish/French army. The battle was so critical because the winner determined who would sit on the British throne, who would wield religious power in Ireland and lastly determine if French dominance of Europe would continue.

The visitors' center was housed in a mansion called Oldbridge House built on the battle site 50 years after the war. The highlight was a huge battleground model with laser lights that moved the troops around the site which showed how the battle took place on that fateful day.

The map of Europe in 1690 showed (in red) the alliance of lesser states - of which William of Orange was one of the leaders - that was formed to stop the aggressive expansion of Louis XIV's France (in blue), which was the greatest European power at the time. France sent soldiers to Ireland in 1690 in order to divert William and his resources from the conflict with France on the European mainland.

The Battle of the Boyne was to be the largest single action between two opposing armies comprised of 60,000 soldiers ever to take place in Britain or Ireland. Both kings commanded their armies in person.

King William’s forces managed to fight their way across the River Boyne and defeat King James who fled south in full retreat. King William of Orange’s victory is still celebrated in Northern Ireland every July 12th with marches by Unionist Orangemen even though the battle actually took place on July 1st. The celebration was moved to 11 days later when the Gregorian calendar was adopted in 1752.

The 1693 painting by Jan Wyck called Battle of the Boyne included all the major players in the battle.

King William, wearing the blue sash and silver star of the Order of the Garter:

The Flight of King James II after the Battle of the Boyne by Andrew Carrick Gow depicted the king departing in defeat. James' attempt to recover his lost throne through Ireland was over and he immediately returned to France where he kept his court as a guest of Louis XIV until his death in 1701.

A painting of the victor, King William III:

The Williamite artillery train was made up of more than forty Dutch and English field guns and mortars. The Jacobite train consisted of twelve French four-pounders and four cannon produced in Ireland.

Flowers still bloomed in late September in the Walled Garden behind the mansion. The gardens of larger houses, as at Oldbridge, were usually enclosed by high walls for protection from the elements and theft. One hectare of garden could produce food for about 25 people and about 5 gardeners were needed per hectare. The gardens supplied the family, servants and sometimes the estate staff with fruits and vegetables all year. The gardens all supplied the house with flowers.

The high walls also created a micro climate which was warmer and less windy than the outside. The walls were covered with fruit trees and glasshouses to maximize the growing potential of the garden.

The Memory sculpture by Michael Warren was made from a fallen oak tree that once stood here in the small village of Oldbridge. It was carved into its present form and placed in the Walled Garden to suggest "memory, linkage and continuity."

At the bottom of the garden were the stables.

This was the River Boyne site where the pivotal battle took place but there was no bridge there then. I know it was crazy to expect to 'see or feel' something from that major battle that took place here so long ago, but to see such a placid river with little traffic just seemed incongruous to me at the time.

We didn’t have a chance to see the General Post Office or GPO when we were in Dublin a month ago so made a beeline for it this time as it was at the center of events that govern Ireland today. In 1916, the GPO was at the core of an major event in Irish history known as the Easter Rising. At that time, Ireland was under British rule and some people wanted to bring about change. They staged a rebellion in Dublin and the GPO was their headquarters in the city. Their aim was to ignite a national rebellion and bring about independence for Ireland.

Against the background of poverty, inequality and social divisions, a range of nationalist, suffragette and trade-union movements struggled to achieve social and political reforms. In 1916, the growing, prosperous, Catholic middle class took up jobs they hadn’t been able to have earlier because of their religion.

There was a huge inequality of poverty still, with most existing on potatoes only. Many people lived in extreme poverty where diseases were rampant. Of every 1,000 babies born, 147 died before their first birthday.

An intense political and cultural awakening in early 20th century Ireland prompted many radicals and activists to mobilize and demand change. Many were involved in the cultural revival but a radical minority wanted to move beyond that, and came to believe in the necessity of a military struggle. The Republicans wanted a complete separation from Britain. Many wanted a new type of Ireland including profound social change.

These men and women took to the streets of Dublin on April 24, 1916. Within weeks, many would have lost their lives in the fight for independence. The GPO staff controlled communication between Ireland and Great Britain. Some employees, loyal to the cause for independence, cut the cable lines to Britain. That was a critical reason why the GPO was chosen to be the go-to location for the rising.

How sad to think that within a week of the rising much of the city's center would be destroyed and, more importantly, 455 men, women and children would be dead, most of them civilians who happened to be in the wrong place at the wrong time.

The Crown Forces were taken by complete surprise when the rising broke out on Easter Monday at the GPO in Dublin. Although there were 20,000 soldiers stationed in barracks around the city, fewer than 400 were available on the morning of the rebellion as key personnel either weren’t in Dublin or were at the horse races.

But the military response was prompt and as the week passed, reinforcements secured key locations. 116 members of the Crown forces died including some police officers.

Retribution by the British was seen as an act of treason. While the initial response of the public in the aftermath of the Easter Rising was largely negative, it was the nature of the British retribution that had the most profound effect on how the rising was viewed and understood by British people.

The initial hostility toward the rebels began to change following the arrest of over 3,500 suspects and the number of court martials. Drawn-out sentences with no jury and trials were held in secret. 90 death sentences were imposed. The drawn-out executions at the Dublin Gaol of the seven men who had signed the Proclamation of the Republic and nine others helped to radicalize public opinion.

The Easter Rising was militarily a failure but 50 key aims were achieved. Perhaps most importantly, the Irish rebels had been successful in capturing key sites around the city and holding British forces at bay for a week.

By the end of 1918, the political landscape was transformed, the Irish Parliamentary Party was obliterated, Sinn Fein was dominant and the home rule project had died.

The military conflict between British armed forces and the IRA from 1919-21 consisted of sporadic guerrilla fighting.

It was paralleled by the efforts of the self-proclaimed government of the Irish Republic to establish a revolutionary counter-state.

In the middle of this, the Government of Ireland Act of 1920 created a separate Parliament for the six counties of Northern Ireland, thereby partitioning the island once and for all.

On July 11, 1921, the War of Independence was brought to an end by a truce and on December 6, Sinn Fein's delegation signed the Anglo-Irish Treaty in London.

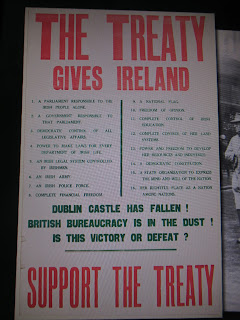

Sinn Fein divided into two factions: those that supported the Treaty and those who opposed it.

During the ensuing Civil War which lasted from June, 1922, until May of 1923, between 1,500 and 2,000 people were killed, with both sides committing atrocities.

A plaque at the visitors' center at the GPO said it was "dedicated to the memory of all those men and women who fought and served in the cause of Irish freedom during Easter Week 1916." This was just a small listing of those people.

Once again, the interior of the GPO looked completely normal with no vestiges of the role it played in the struggle for Irish independence over a hundred years earlier.

Our last night in Ireland, for old times' sake, we ate at the same restaurant we did on our first night!

Posted on March 11th, 2020, from Anuradhapura in northern Sri Lanka before heading south in the morning for our last day in this country and, we hope at least, continuing our long adventure through Asia and the Middle East in the age of the coronavirus!

No comments:

Post a Comment